Month: May 2019

Full sketchbook contents for FMP

An extensive list at the material I looked at for this project:

Documentaries:

- In Defense of Food

- Sustainable

- Cooked

Books:

- In Defense of Food by Michael Pollan

- Vegetables, Soil & Hope by Guy Watson-Singh

- The Pedant in the Kitchen by Julian Barnes

The war against plastic

“We owe a debt to those of the past that created the opportunities that we have today, and we can only repay that debt to people of the future, but with our repayment of that debt, our life becomes better”

John Ikerd (Professor Emeritus of Agricultural Economics at the University of Missouri)

There has recently been a lot of outrage against single use plastic, and rightly so. The quantities of throwaway plastic in supermarkets alone is staggering. A survey conducted by a campaign group in partnership with the Environmental Investigation Agency found that the top 10 UK supermarkets are currently putting out around 810 000 tonnes of plastic on the market every year, which is discarded after one use. None of this is recyclable and it is harming our sea life. Plastic pollution is truly a crisis.

The worst thing is, we don’t even need this plastic in the first place. Where I grew up in France, supermarkets sell their fruit and veg loose and shoppers can bring their own bags and pick up however much they need. Here in the UK, everything has to be wrapped in useless plastic. Thankfully, more and more supermarkets are selling some fruit and veg items loose, especially carrots and potatoes. There is a lot of pressure from Greenpeace for supermarkets to have a clear plastic reduction target plan, and some of them have. Iceland, Morrisons and Asda seem to be the ones most set on reducing single use plastic, according to the recent Greenpeace ranking. The worst ones are Sainsburys and Coop.

With this knowledge in hand, each of us can take part in the war against plastic. If supermarkets fail us, we can turn to local farmer’s markets, community gardens, or even veg box schemes (Abel & Cole and Riverford being the two main ones). We have the power to send the message to big retailers that we want to change our food system, and this message is already reaching them loud and clear, so let’s keep going!

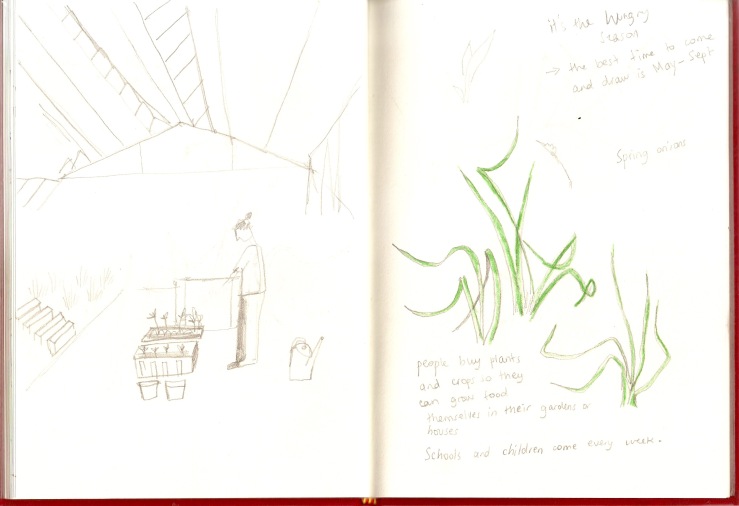

Community gardens and allotments

A great alternative to expensive organic products is to be part of a community garden or an allotment. There are so many of these projects around us but we don’t always realise it. I found out not long ago that there was a community greenhouse in the park I always go to next to where I live.

The great thing about community growing is that not only do you have a very close connection to your food but also to your local community. The best way to change the way we think about food is to do it collectively, and talk to each other. Community gardens also typically work with schools to teach children about growing food and eating fresh fruit and veg, which I think is incredible. I wish I had been taught the importance of good food when I was at school.

You really couldn’t do better in terms of local food, and meeting the people who grow it. Here are a few projects around London:

- Growing Communities, Hackney. http://www.growingcommunities.org

- Brockwell Park Community Greenhouses, Herne Hill. http://www.brockwellgreenhouses.org.uk

- Walworth Garden Farm, Kennington. http://www.walworthgarden.org.uk

- Surrey Docks City Farm, Rotherhithe. http://www.surreydocksfarm.org.uk

- Urban Growth Learning Gardens, Brixton. http://www.urbangrowth.london

Those are just a few but there are so many more!

Growing with life (save the earthworms!)

Part of the organic farming philosophy is to use natural alternatives to pesticides. Whilst conventional agriculture relies on chemicals to grow higher quantities of produce, the organic farmer uses a science called biology. Pesticides disrupt natural life, but by using biological tactics to deal with weeds without using chemicals, organic farmers do far less harm to the biodiversity living in the soil.

Some organic farms have actually found that yields can be improved when the soil is healthy after going through periods of draught. We are also losing a lot of arable land due to soil erosion caused by intensive farming. The UN actually called for intensive farming to be stopped when it was revealed that it was destroying 24 billion tonnes of fertile soil a year. Over the long term, organic methods can be as high-yielding as conventional farming.

We have been treating soil like dirt, but it is agriculture’s most precious resource. Soil is where life grows, so how can we keep spraying it with products designed to kill all life, then eat from it?

Within the soil live earthworms, and although they don’t seem like it, they are incredibly important. Through their movements they are continuously mixing, airing and draining the soil, enabling it to recycle nutrients and create natural fertiliser. We should let earthworms wriggle in peace in the ground, and our food will be all the better for it.

Food for profit

Industrial foods are designed for profit. The industry isn’t concerned with how well humans are being fed, and what is sustainable for the planet. They are concerned with creating the most profitable system possible. This is why we can’t always trust processed foods, even when they claim health benefits.

When food was first industrialised in the 1950s and 60s, it seemed like a huge progress: it promised to improve efficiency in producing larger quantities and therefore providing food security. But we now know all of the downfalls that come with these new hybrid products, with long lists of ingredients no one can pronounce. They are processed to taste good so they generally contain corn syrup which boosts the risk for heart disease, diabetes and cancer. Intensive Agriculture is one of the main culprits for climate change. We grow a lot of one type of crop in one area, which means that if it fails, the most vulnerable parts of the world face a food crisis (which is the case right now).

Even though food industrialisation saved many lives and stopped rationing after the Second World War, I think we have gone too far and we are now realising we need to change the way we think about food. Even though action has to be taken by leaders and manufacturers, actions on a smaller scale can be taken by us all. The main ones are to eat smaller portions, eat less red meat and try to eat seasonal and locally produced food.

Oh no, I burned the onions again

“Cooking is the transformation of uncertainty (the recipe) into certainty (the dish) via fuss.” Julian Barnes, The Pedant In The Kitchen

I’m really impatient. When I cook, I always like to do other things at the same time and so often enough, I end up burning something. Cooking can be quite an intimidating thing. Beginners might think it needs a lot of skill and is very difficult, which is true for Michelin star chefs. But for the average person, it’s okay to mess up sometimes and to learn through trial and error.

Some people might say: “Oh cooking isn’t for me, I’m just not very good at it”, to which I say: Me neither!

By advocating cooking I don’t want to alienate the people who think they can’t do it. I can’t do it either, most of the time, and I often mess up. But I still enjoy the process, and when it does go right, it is extra satisfying and I enjoy it even more.

GMOs VS Organic

Genetically Modified Organisms are designed to be resistant to herbicides or even sometimes to produce their own insecticide. Most sweetcorn crops in the US are engineered to resist to Roundup (Monsanto’s glyphosate pesticide) and to produce Bt Toxin, their own insecticide. The biotech companies who are creating these GMOs insist they are safe, and indeed no existing study really proves that they aren’t. This is a recurring problem in the organic food debate, critics say no real long term studies have actually been conducted to try and prove the toxicity of GMOs and pesticides. Companies that produce these GMOs also test their own products, and it is hard to believe that they would be completely objective sharing the results. Contradicting this, major independent science organisations around the world have all concluded that GMO crops are safe (according to the Genetic Literacy Project).

Although claiming to be an objective authority on science, the Genetic Literacy Project was named an ‘industry partner’ by Monsanto, that could help protect the reputation of Roundup. Indeed, Monsanto turned to groups like the Genetic Literacy Project in an effort to discredit the World Health Organisation who condemned Roundup as a ‘probable human carcinogen’ in 2015.

And so here were are back to square one. How do you navigate all of this contradictory information? It is very hard to find transparency in debates with such high stakes surrounding products with big markets. However, I have generally found that any organisation or study declaring pesticides and GMOs safe have some affiliation with Monsanto, so I am choosing the organic side for now. Trusting naturally grown food is an instinct that would appeal to any human being, and the amount of misinformation about GMOs comforts me more towards the idea that you can only trust the organic methods.

Navigating supermarkets

American food writer Michael Pollan said : “The healthy food is quiet, so buy the quiet foods in the market”.

I like this quote because I’m interested in the idea of appreciating food in its least transformed state. There can be so much distance between us and the food that we eat, sometimes if we buy overly processed products we might even barely be aware of what is in them. The issue is that there aren’t many marketing campaigns promoting leeks, or there aren’t adverts on buses for big brands of oranges. Instead, what gets advertised is quick, convenient, ready to eat food, with little thought as to where it comes from and what it was made with. This is why I want to promote the ‘quiet foods’. The unprocessed, natural stuff that was grown then sold directly. With debates surrounding sustainability and food, the first step in eating better is knowing what we are eating. The answer for me isn’t to trust pricey health foods with labels promising less fat and more fibre. When we choose raw ingredients which we cook ourselves, that is the best way to connect with what we are eating and appreciate where it came from and how it was made. That way, we can stop eating all the strange chemical additives that no one reads on the back of food packets. To me, that is the true definition of healthy food.

The climate footprint ladder

I read a great article on the New York Times that was all about how the food we eat impacts climate change.

There is a fine line between educating and guilt tripping and food debates attract a lot of outrage. Vegetarian and vegan diets seem to be more and more popular, and when you look at the environmental impact alone of meat and dairy, it makes sense (not to mention animal welfare, but that is another debate). Whilst I’m an advocate for these diets, I don’t think we should be screaming at people to stop eating meat and cheese. The conversations that I find a lot more refreshing are the ones that give more sustainable solutions that fit every type of diet.

Eating less meat is definitely on the to-do list for anyone that wants to reduce their carbon footprint, but that doesn’t necessarily mean cutting it out altogether. There are meats that have a smaller greenhouse gas impact than others, and the way meat is farmed is also important in my opinion.

When choosing what to eat (and what not to eat), I think the best solution is to look at how much different food types impact climate change and try to reduce the consumption of certain groups to an extent that feels right for you. The New York times article included a chart with the foods that have the largest greenhouse impact, which I have translated into illustration:

Here’s the link to the article: